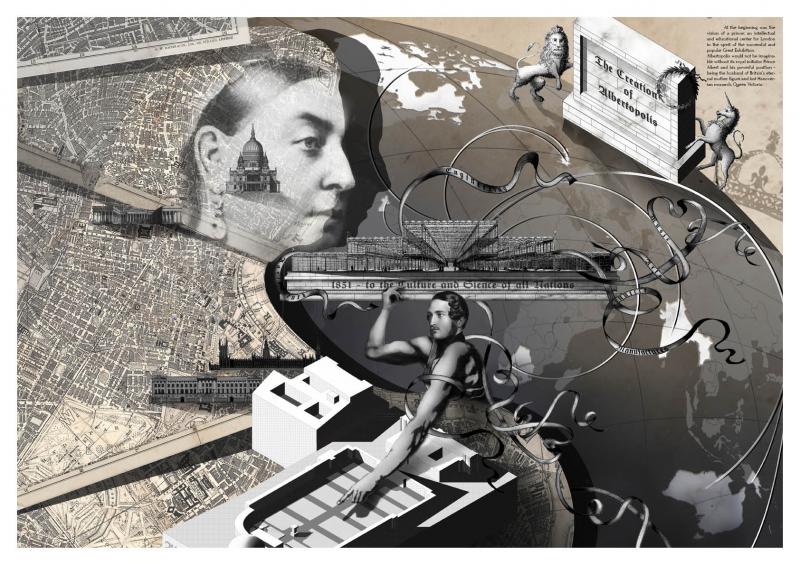

After the Great Exhibition of 1851 at the Kensington corner of Hyde Park had become a great cultural and financial success, Queen Victoriaís husband, Prince Albert, developed the plan for an area devoted to the arts, sciences and industry - a comprehensive intellectual centre for London where teaching institutions and collections are placed next to each other for a direct specialist and public utilization of knowledge. Albertopolis.

Following the Princeís vision, the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 purchased an estate in South Kensington, originally a suburban area of fields and horticulture. A new road network was development with Exhibition Road and Queens Gate as two major urban axes and the idea of a central garden surrounded by the desired institutions.

Ever since, Albertopolis did not grew over itís initial boundaries yet developed in a restless evolution of appearing and disappearing institutions in competition for space and program to the cluster we know today.

The implementation of Albert’s noble idea - a cultural center to educate the masses - has to be understood as an act of incredible power in a still royalist spirit of the Victorian era. This almost patronising dimension can be experienced unto this day. The regulations which try to explain how to function within the collections; the uncounted buttons we have to push in order to gain more information; the plastic dummies, animated and excessively lit; signs trying to teach accompanied by restaurants, shops and all the other characters from Baudrillard's nightmare - at the highpoint of Albertopolis’ popularity, the thousands of visitors in their consumption of ready-to-take-away information still appear strangely passive. Furthermore, the physical neighborhood of universities and museums, once understood as a stimulation for interaction and collaboration seems outdated in a time of communication media Prince Albert could not have dreamed of.

Once planned as a fertile center of culture, science and education and regardless the treasures that still can be discovered within its walls, Albertopolis today presents itself as a cluster which primarily produces noise.

Regarding such popular spirit, this abstract will attempt to consider the unpopular within Albertopolis, the lost and forgotten, the demolished and unbuild. The search for a language to memorise the outsider will point toward a folly outside the walls.

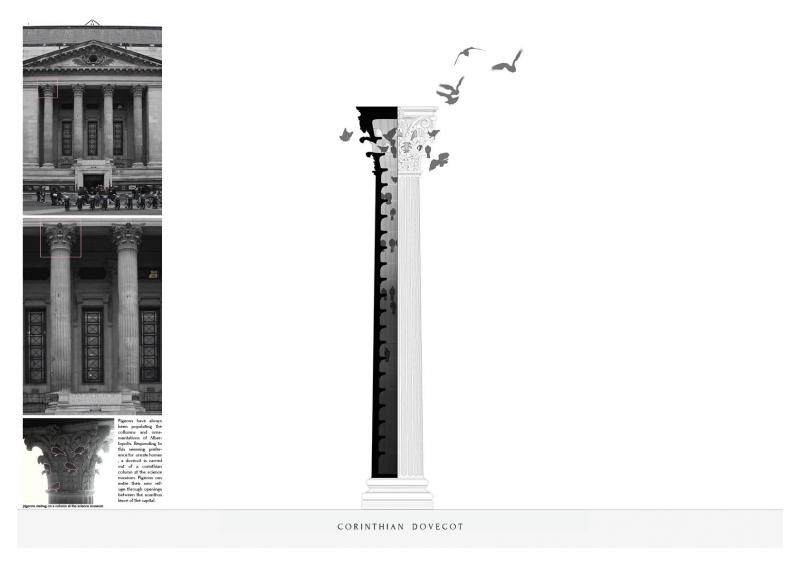

Corinthian Dovecot

In search for the unpopular within Albertopolis - a home for the pigeon population as an ambassador of the outsiders.

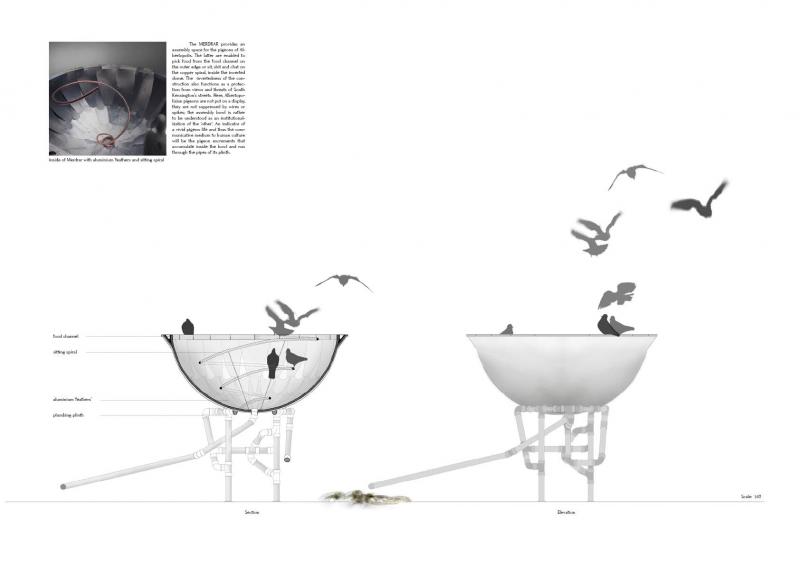

Elements for a Pigeon Institution

Merdrar

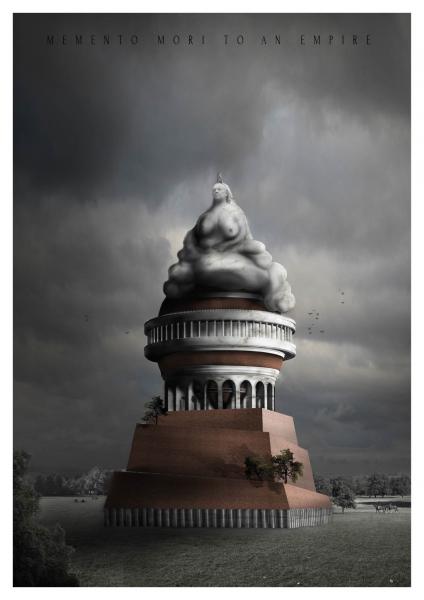

Memento Mori to an Empire

A monument to cover the Albert Memorial and by this gesture bury Albertopolis.

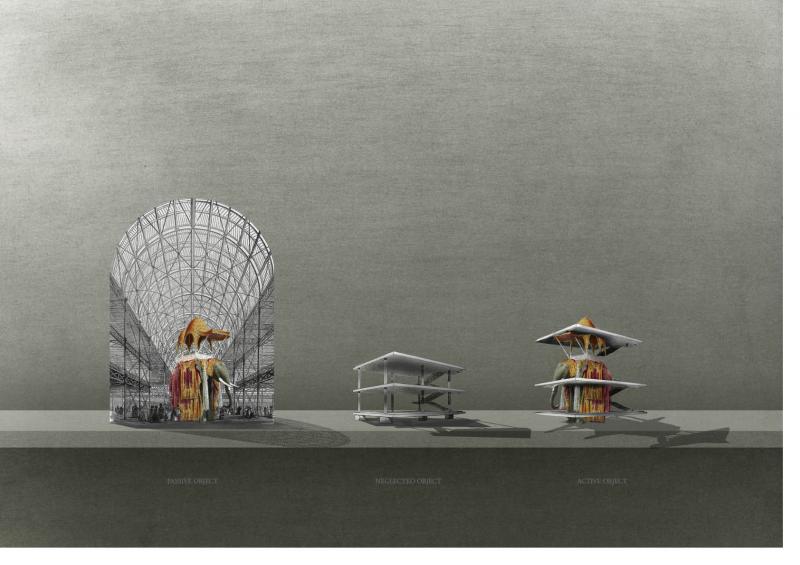

Typology for a Monument to the Outsiders

The language for a monument to the unpopular, the 'outsiders' presumably has to differ from Victorian styles. Here, the trace of the unpopular object - regarding Albertopolis the fragment of the unbuilt or demolished - itself is 'activated'.

Left-Over Monument

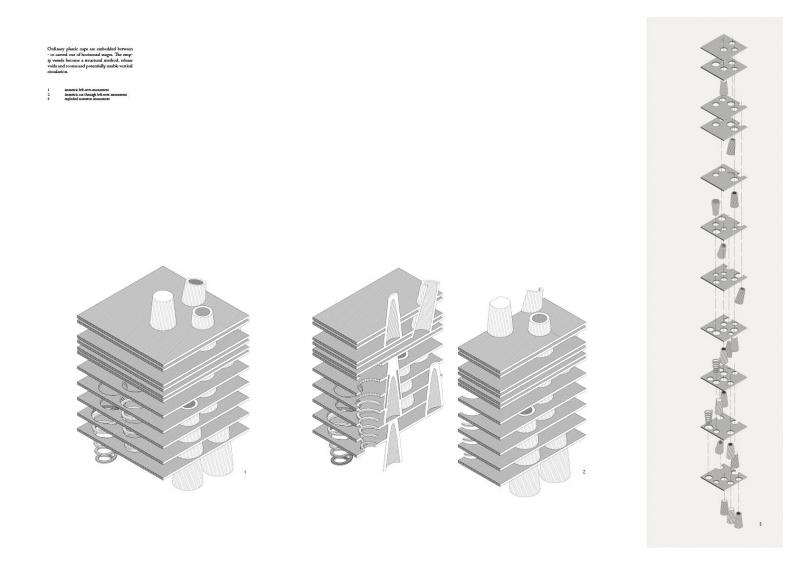

The Typology for a monument of activated objects is further explored by an explorational model of layers and cups.

Folly Outside The Walls

Interpretations of fragments of unbuilt or demolished buildings within Albertopolis are embedded between the (time) layers and form a growing monument - a folly really - celebrating the unpopular.

Section through Albertopolis and the Folly

Built on the central axis through the Natural History Museum, Queens Tower, Royal Albert Hall and the Albert Memorial, the Folly of Outsiders leaves Albertopolis behind and finds its new context in Kensington Gardens - outside the walls.

Albertopolis within the city versus a folly in the park.

Folly Outside The Walls

section